Welcome to the 80th Pari Passu Newsletter.

Today, we are learning about the topic of the moment: “Synthetic PIK”. Truly exciting stuff going on in the world of credit. To understand what brought us here, we need to take a step back to a few years ago.

During 2021, we saw the boom of the private credit industry, which provided capital to companies that were too large or stressed for commercial banks to lend to. With this added risk came a substantial reward as private credit offered yields upwards of 10%. Since then, the private credit industry has continued to develop, and investors are continually seeking avenues to increase their returns. Over the past two weeks, one of the hottest topics has been synthetic payment-in-kinds (PIKs), a lending method that allows companies to service their debt with more debt (with a spin), thereby increasing returns for investors. Today, we will look at the evolution of the private credit industry, the creation of the synthetic PIK, and the implications of this “creative” financing structure.

Automate finance ops for your portfolio

Ramp works with over 25,000 businesses to help them run their companies more efficiently. We recognize the critical role that finance automation plays in driving value creation for PE firms. With Ramp, you can reduce operating expenses and drive efficiencies across your portcos with real-time spend visibility and Al-powered insights. Time is money. Save both with Ramp.

Automate your finance operations, all in one platform.

→ Corporate Cards

→ Expense Management

→ Travel Management

→ Accounts Payable

→ Procurement

Join the hundreds of private equity and venture capital firms already partnered with Ramp

The Evolution of Private Credit

Before diving into synthetic PIKs, it is essential to understand the context in which they are used, which traces back to the private credit industry. Private credit ranges across the capital structure, from senior secured loans to junior unsecured debt. The main selling point of this asset class is its resilience throughout economic cycles, as demonstrated in Figure 1. As the name implies, private credit is not publicly traded, offering certainty and increased execution speed during volatile public market periods. Due to this illiquidity, the returns of this asset class have proven to be the highest across debt investing strategies over the past few years.

The private debt asset class was sparked due to the changes in the financial industry following the Global Financial Crisis. Commercial banks retracted their traditional bank lending arms due to increased regulations and required reserves. This created an inherent disconnect between supply and demand. Many middle market companies, either too small or too stressed for commercial banks to lend, sought alternatives to fuel their growth, and private credit filled this gap in the market. These companies found the public markets too burdensome. With the excess capital held by family offices, these companies were willing to bear increased interest rates and tighter covenants to get private capital.

However, the industry experienced a boom in 2020-2021, and has seen sustained growth ever since. In March 2020, the credit markets began to grind to a halt, and we saw both investment grade and high yield spreads explode. Companies of all sizes were in need of capital, and there was a significant amount of uninvested capital, known as 'dry powder ', held by family offices and small institutions that could be lent to these companies. These private credit lenders took advantage of the high spreads and low capital to obtain large returns, developing private credit into a $2tn market.

When the interest rate hike cycle began in 2022, many companies became stressed/distressed, and private credit lenders provided capital when commercial banks were unable to take on the increased risk. Lending to stressed companies can generate high yields, with private credit returns reaching over 20% in some cases [1]. Many professionals consider the current period the ‘golden age’ of private credit, as the market is favorable for opportunistic credit strategies.

The relationship between private credit and synthetic PIKs, and PIKs in general, relates to the illiquidity of the capital and the leverage the lender has. Paid-in-kind capital has existed for many decades. Debt across the capital features some form of interest rate, whether floating (changes with the underlying SOFR/Prime rates) or fixed rates. Interest rates determine the interest payments per period, and missing one cash payment constitutes a form of default. PIK circumvents this issue, allowing borrowers to add their interest payment to the total debt outstanding on the balance sheet and pay it when the debt fully matures. Let’s look at an example to explain why this structure entices lenders.

Let us say we have a debt of $100mm with $10mm in interest payments per year (10% interest rate) for 4 years. Without PIK, the company would have to pay $10mm in cash per year for four years, then the $100mm at the end of the fourth year.

Under PIK interest, the $10mm of yearly interest would be added to the total debt balance each year. So, at the end of year 1, the total debt balance would be $110mm. However, in year two, the company would have to pay interest on the $110mm rather than the $100mm, increasing the total debt outstanding to $121mm in year 2, $133.1mm in year 3, and $146.41 in year 4. In this case, both interest rate equal 10% (but it is important to notice how PIK case leads to a higher balance given interest is compounded over the years).

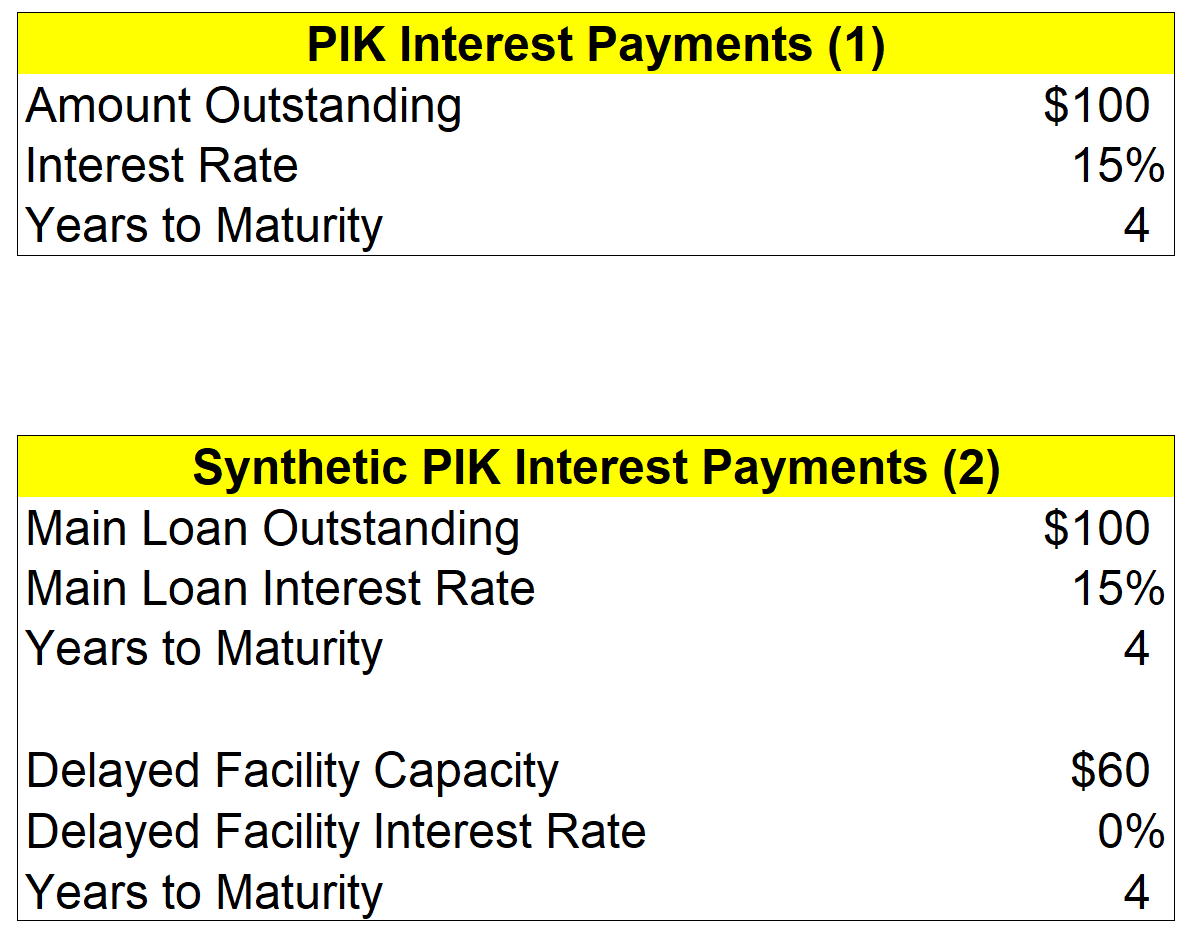

In addition to the compound effect, PIK rates are often higher than cash rates to compensate for the increased duration risk. Thus, a lender might require even 15% per year of interest expense if the company uses PIK. This makes PIK financing even more attractive (and risky) from a creditor perspective.

There is an inherent risk in pushing back all your interest payments back to the maturity date for the lender, and this is why PIK is typically only used for stressed companies to extend their runway and hopefully turn around the business. In recent years, we have seen the PIK transformed into the PIK toggle, which offers companies the option to either pay in cash (if possible) or use PIK as needed. Due to the flexibility of private credit mandates, PIK is more commonly seen in private debt. As interest rates have stayed elevated since 2022 and are expected to stay elevated for the short-mid term, we are seeing more companies enter into stressed/distressed situations, and private credit firms are looking for ways to continue receiving the returns they have seen over the past four years [1]. This has led to the innovation of the synthetic PIK.

What is Synthetic PIK, and How Does It Work?

Synthetic PIKs allow companies to pay interest rates without the 'in-kind' portion. Synthetic PIKs still accrue debt on the balance sheet as interest expense is due, but lenders still receive cash interest per period. How is this done? With two pieces of debt: a primary loan used as capital to service the company's operations and a secondary, delayed draw-down loan used to service the interest payments. Let's break down each component with an example [2].

Let's say we again have a term loan of $100mm provided to a company for their operations. This debt has an annual interest rate of 15% and matures in 4 years - meaning the company owes $15mm each year plus the $100mm of principal in year 4. Let's say that the company we have lent to cannot service their interest expense. One way we could circumvent this is via PIK or create a second facility meant to service the interest expense solely.

This facility is typically structured as a delayed draw-down facility. A delayed draw-down facility is a term loan that allows a borrower to withdraw funds over time rather than getting the total sum at issuance. Typically, the withdrawal time and rate are reviewed every period, whether six months, one year, etc. The total debt drawn is still due at maturity [2].

In our example, let's say that this delayed draw-down facility has a total capacity of $60mm, and it is agreed that $15mm can be drawn annually. Each year, when interest payment on the $100mm is due, the company will withdraw $15mm from the delayed draw-down facility. This costs the company nothing, acting just like a PIK. The differences can quantitatively be seen below in Figures 2 and 3.