Celsa Group: A Case Study in Spanish Restructuring

Welcome to the 66th Pari Passu newsletter.

A few weeks ago, we covered the ongoing restructuring of Lumen. Today, we are back with another asset-heavy restructuring lesson: the Spanish steel manufacturer Celsa.

On the 4th of September 2023, Spanish judges ruled that ownership of the company would be transferred to creditors, ending a drawn-out three-year battle.

But what is Celsa? And how did they end up giving the keys to creditors? Why should we care? To understand the intricate workings of one of Europe’s most high-profile restructurings in the past decade, we must first learn more about the company at the center of this dispute.

Part 1: A Deep Dive into the 2023 Restructuring

Company Overview

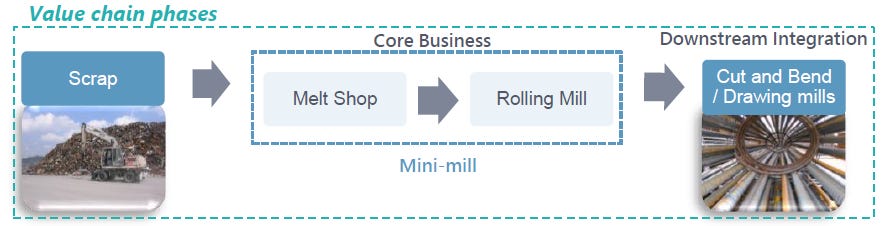

Headquartered in Castellbisbal, Spain, Celsa Group is one of the largest long steelmakers in Europe. It is the 1st producer of corrugated products, the 2nd producer of profiles and bars, and the 3rd high-end wire rod producer in Europe. The Company, formerly privately owned by the Rubiralta family, operates in Spain, in France, the UK, Poland, and the Nordics. The Company uses Electric Arc Furnace technology in its processes, and it is present across the entire steel value chain including scrap, melt shops, rolling mills, and cut and bend. Celsa mainly serves the Construction and Automotive industries, but also the Agriculture, Oil & Gas, and Energy industries.

How did we end up here?

Over the last ten years, they underwent two restructurings, one in 2013 and one more recently in 2023. Back in 2013, Celsa was badly affected by poor economic conditions in Spain, and ended up refinancing €2.5bn of debt through a “Spanish Scheme” process, with 91% of lenders supporting the deal [1]. At the time, most creditors were banks such as Barclays and Santander [2], but this would greatly change in 2020, as almost all of them needed to sell their positions at significant discounts upon the distressed situation arose. Celsa’s operating subsidiaries across Europe have also undergone major refinancings, with Celsa Huta, their Polish subsidiary, refinancing Z2.3bn ($634mm) of debt into two new facilities [3].

What happened in 2013?

The “Spanish Scheme” was a restructuring process introduced in 2011 by legislators. It was initially regarded as helpful to struggling businesses wanting to pursue out-of-court solutions, but then opinion quickly changed and the Scheme was later criticized for being too rigid. In particular, the scheme was tilted in favor of secured lenders who could enforce their debt claims in almost all cases making companies with significant secured debt harder to restructure. In the case of Celsa in 2013, the company decided to use the Scheme to cram down on 9% of secured creditors who were opposing the scheme. Courts ended up approving this, stating that the opposing creditors’ secured debt was actually unsecured. The decision ended up coming down to a one-word difference, with the judge stating that creditors were “formally” but not “materially” secured, meaning that they couldn’t enforce their security and claim Celsa assets in the event of a default and were thus unsecured.

Another point of clash in the process was the extension Celsa would receive on the terms of the debt, which the courts set at 5 years while the Spanish Insolvency Act had set a maximum of 3 years. In response, judges clarified that the maximum term of 3 years set out by law only applied to how long lenders would have to wait before enforcing and collecting their debt claims from the company rather than giving the company a longer runway to repay the debt back, effectively allowing the company to retain the new 5 years maturity. What this meant for potential future creditors was that they had to keep a close eye out for judge decisions, especially their interpretation of the law and the implications for lender recoveries. [1]

What happened during the pandemic?

In 2020, as COVID-19 worsened, Celsa again faced operational issues and exceeded its leverage ratio covenant in Q2 2020. Given this initial covenant breach, if they exceeded leverage for a second quarter in a row, creditors could force the company’s €1.2bn of convertible debt to convert into equity under Celsa’s covenant agreement. This was significant since it could allow holders of that convertible debt to take over the company if they ended up holding most of the equity after the conversion [4].

In contrast, the “jumbo” debt did not grant a strategic position to the creditors. This form of financing represented the firm’s €1.4bn term loan created after multiple individual term loans were rolled up together in Celsa’s 2017 refinancing. Highlighting the refinancing is important since there was a mechanism implemented under which convertible debt could be converted into jumbo debt (rather than equity) if leverage fell below 4.5x. Adding complexity to the situation was a Spanish ruling earlier in 2020 which protected Celsa from creditors who held jumbo debt and kept trying to enforce any defaults. Effectively, this meant that any defaults on the jumbo debt through a covenant breach or missed payment could be waived if it ended up in court. [5]

In June 2020, bondholders of Celsa’s “jumbo” debt tried to find a different solution and presented a restructuring plan that involved converting €700mm of convertible debt into 49% of equity while the Rubiralta family would maintain a 51% stake. Given the favorable restructuring dynamics, the company declined. [4]

Another side of the story worth diving in is the question of solvency. Being solvent was important to Celsa’s argument that they were a company able to operate without the need for a reorganization, while the appearance of insolvency would weaken this position. Equally, insolvency was a critical point in the new Spanish restructuring regulation where lenders could ask courts to approve their restructuring plan when the company was opposing it under the condition that the company had to be insolvent. Celsa’s creditors claimed that the company was insolvent and unable to meet debt payments even before COVID-19, while the company argued that the pandemic was a big catalyst such that they made a loss of €144mm in revenue and a 45% decrease in operating income which was why they company did not have the cash to repay its debt. [6]

The Spanish government steps in

During the pandemic, Spain’s SEPI (state-owned industrial holding company) started a €10bn COVID-19 emergency fund through which many sponsor-owned companies such as Areas, Vivanta, and Abengoa were able to access emergency rescue funding. Celsa UK had benefited from a similar British emergency fund, securing a £30mm public sector loan with warrants that could give the government a 20% stake upon conversion [7]. Meanwhile, in Spain, Celsa was originally in line to receive €200mm from SEPI but later increased their request to €800mm, asking SEPI to form €550mm of investment as a convertible instrument [8]. This could help Celsa since, if they defaulted on the convertible loan, the Spanish government could take an equity stake in Celsa and dilute how much creditors could theoretically own in terms of equity. In contrast, if the investment was a traditional loan, a default would be treated the same as adding to the massive €2bn+ debt pile, complicating the restructuring even further since the government would become an important creditor in the process and would have to be taken into consideration by creditors when putting forward proposals.

Celsa was ultimately successful in receiving the €550mm bailout from SEPI; as expected this increased their negotiating power and they continued to reject creditor proposals citing that they were incompatible with the strict SEPI regulation. This back-and-forth ultimately drew out the restructuring process even longer, which gave Celsa time to bounce back from the pandemic. This materialized when Celsa started posting record sales due to export tariffs imposed by China and Russia on the steel industry in late 2021 achieving all-time high performance in FY2022 when inflation skyrocketed. This was crucial in forming a picture of a solvent Celsa, which went a long way to improving the market opinion of the company, and Celsa’s debt started to trade up.