Welcome to the 89th Pari Passu Newsletter.

Almost exactly two months ago, we published the first deep dive on Synthetik PIK.

Today we are talking about another exciting topic of the restructuring world: Double-Dips. While others have already covered this topic, I believe Pari Passu has taken a different approach and will explain this concept as easily as possible so that everyone will be able to understand its dynamics.

Today’s restructuring world is highly complex. Uptier and Dropdown (our Envision Deep Dive provides a great explanation of these concepts) were the first versions of liability management transactions that we saw and opened a new path for out-of-court restructurings. In the past few years, we have seen a new breakthrough in liability management transactions: double-dips.

Starting with the At Home Group, more and more companies are resorting to this maneuver to provide liquidity and help extend a company's runway. However, drop-downs have actually existed for over a decade - just “accidentally”.

Today, we are going to go into a deep dive into the history of double-dips and the various iterations we are seeing in the modern day.

But first, a message from 10 East

10 East, led by Michael Leffell, allows qualified individuals to invest alongside private market veterans in vetted deals across private credit, real estate, niche venture/private equity, and other one-off investments that aren’t typically available through traditional channels.

Benefits of 10 East membership include:

Flexibility – members have full discretion over whether to invest on an offering-by-offering basis.

Alignment – principals commit material personal capital to every offering.

Institutional resources – a dedicated investment team that sources, monitors, and diligences each offering.

10 East is where founders, executives, and portfolio managers from industry-leading firms diversify their personal portfolios.

There are no upfront costs or minimum commitments associated with joining 10 East.

Background

The easy money era – which stemmed from the Fed’s now-infamous Zero Interest Rate Policy, or ZIRP – resulted in a near-decade-long stretch of abysmal returns for many distressed investors. SOFR, or LIBOR then, was near zero, and many (questionable) businesses could easily access capital markets to raise/refinance debt. This meant the “good company, bad balance sheet” model that drove the rise of distressed investing was replaced with (generally) “bad company, horrendous balance sheet” situations.

However, distressed investors’ loss was private equity’s gain. Low interest rates allowed sponsors to leverage companies heavily and minimize equity contributions, leading to elevated returns and a massive expansion in the asset class post-GFC. Lenders seeking a modicum of yield were forced to loosen credit docs to participate in LBO financings, which generally syndicated the most expensive paper. This was also true of syndications involving non-sponsor-backed debtors with similarly unwieldy capital structures.

Consequently, distressed investors were forced to purchase paper on the secondary market without protections to keep debtors in check. The clearest example was the rise of creditor-on-creditor violence, or liability management exercises (LMEs) that sprung up directly before/during the pandemic.

The emergence of uptiers and dropdowns created an environment wherein creditors willing to play ball with debtors could have their recoveries augmented in the case of an (almost) inevitable filing. In contrast, non-participating creditors received close to nothing. Although these transactions allowed debtors to extend their liquidity runway and sponsors to demonstrate their willingness to retain equity, they also strained relations between them and creditors, sometimes resulting in lengthy litigation that further leaked value.

To counter this, restructuring advisors referenced the past to create a transaction structure that allowed heavily indebted companies to access financing while not (immediately) priming existing or non-participating creditors. This structure is referred to as a double-dip and is the subject of today’s article.

Definitions

In order to understand the mechanics of double-dips, let’s start with reviewing a few key terms:

Restricted Subsidiary: This is a subsidiary that must adhere to certain covenants or restrictions imposed by the parent company's debt agreements. These restrictions can limit the subsidiary’s ability to incur additional debt, make investments, or pay dividends.

Non-Guarantor Restricted Subsidiary: This means that the subsidiary is not guaranteeing the parent company's debt. If the parent company defaults on its debt, creditors cannot directly claim assets or cash flows from the non-guarantor subsidiary to satisfy the debt.

Unrestricted Subsidiary: This is a subsidiary that operates independently of the restrictive covenants imposed by the parent company’s debt agreements. It has more freedom to engage in activities such as incurring debt, making investments, and paying dividends.

Intercompany Loan: As the name suggests, an intercompany loan is a loan given from one entity in a company's corporate structure to another.

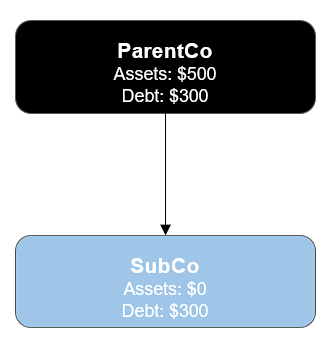

Downstream Guarantee: A downstream guarantee occurs when an entity provides a guarantee (secured or unsecured) to another entity sitting lower in the same corporate structure. Looking at Figure 1, we can see how this works. Without a guarantee, ParentCo’s debt would be unimpaired and SubCo’s debt would receive 66.6 cents. However, with a guarantee, the debt is now treated pari passu, and both debt holders receive 83.3 cents. Downstream guarantees are common when an entity sitting lower in the corporate structure has little to no assets, as demonstrated in Figure 1.

Debt capacity: Refers to the maximum amount of debt a company borrows.

Lien capacity: Refers to the extent to which an asset can be used as collateral for securing a loan.

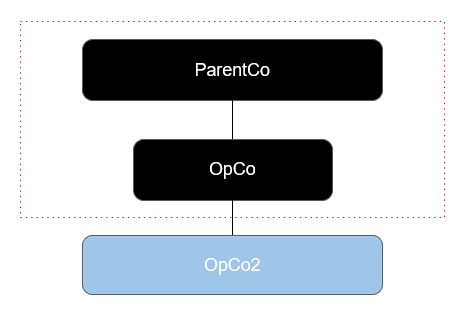

Inside vs. Outside the Credit Box: This phrase refers to the ‘location’ of an entity in a corporate structure and its associated restrictions. Referring to Figure 2, we can see inside the red box (i.e the credit box) exist the ParentCo and OpCo. In each corporate structure, the parent company typically has the tightest covenants in their credit docs. Being inside vs. outside the credit box drastically affects how an entity is subjected to these covenants. In Figure 2, because OpCo is inside the box with ParentCo, it is subject to the ParentCos covenants. These restrictions involve the ability to raise debt and transfer assets, among other things. However, because OpCo2 is outside of the credit box, it is not subject to the ParentCo’s covenants, making it easier to transfer assets and raise new capital without breaching any covenants.

How does a double-dip work?

At its most basic, a double-dip functions by doubling the value of claims a particular creditor can assert in Ch. 11. Mechanically the transaction (again, at its most basic) is structured as follows [1]:

A creditor, or creditor group, provides a secured loan to a non-guarantor subsidiary whose proceeds are transferred to a restricted guarantor via an intercompany loan.

The secured loan then receives a downstream guarantee from the restricted guarantor, making it pari with any existing secured debt. This comprises the first claim, or dip.

The second dip comes from an intercompany loan. The non-guarantor restricted subsidiary upstreams (transfers) the loan issuance proceeds to the Parent Company. In exchange, it receives an asset (the intercompany loan receivable) which acts as a second claim.

To make this easier to understand, refer the following steps to the associated point in the double-dip structure depicted in Figure 3.